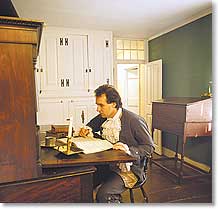

Simeon Perkins (1735-1812) came to Nova Scotia from Connecticut in 1762, shortly after the death of his first wife. Although Perkins came from an upper-class background and had aspirations of grandeur, his house in Liverpool was simple and built for a widower. Perkins focus when he came to Liverpool was his business. He kept a diary from 1766-1812. These stories told by his ghost are based on things he said in that diary.

On being a Planter

“I was born in New England - in Norwich, Connecticut. I was trained to be a merchant and became a partner in a trading company. We decided to exploit the ample natural resources in Nova Scotia - fish and lumber were our primary interests. The possibility of this exploitation increased tenfold after the Acadian population had been expelled from the province and New Englanders were invited to settle here. “Planters” they called us. The first Planters, mostly from Massachusetts, sailed into this Harbour in 1760. I arrived two years later - a Planter from Connecticut. I was young and agreed to move, to establish our concerns in Liverpool. That was 1762.”

On his Business

“I make my living in a number of ways, but mostly by trade, as do most of the town’s inhabitants, in one manner or another. Much of the fish we trade is local - mackerel from Margarets’ Bay just this side of Halifax, and cod out on the banks, or English herring right here in our own river. As for lumber, timberland is everywhere, and most townsmen of any resource have tree lots. There are several sawmills on the rivers. I own one at the Falls – you know it as Milton – where millions of board feet of lumber are sawn for export.

I now mark 41 years in Liverpool - years filled, “on the whole with more business misfortunes than any other person in the place by losses at sea, the bad debts, etc.” Some would say I am more generous than is good for business. A case in point would be salt - the very lifeblood of the fish trade. “Salt is ofttimes very scarce, yet I lend and sell a little almost every day, tho I have not any to spare.” Herring, out of the river here - if I were to take 100 barrels, I could sell every barrel but, instead, I give many “to people for their assistance.””

On Shipbuilding

“I go to the great effort of building ships. Now I am not unique in this - there are many ship builders and yards in Liverpool - the same for other ports in Nova Scotia. But for my part, I have constructed a dozen vessels over the past years. Brigs and schooners for the most part.”

On Privateering

“In the strict sense, I must tell you that the King’s English would define a privateer as a sailing vessel, rather than those who command them, or own them. By unhappy circumstance I fell into the latter category. Indeed, this story of privateering overall, in my estimation, is infused with great “melancholia.”

The Revolutionary War made ‘enemies’ of siblings as Nova Scotians, and specifically the people of Liverpool, trading concerns here were intimately tied up with the American states. When American privateers began to harass what shipping we attempted and began to raid our communities - coming right into our harbours - Lunenburg and other towns suffered as did Liverpool - well, we felt we had no choice but to reciprocate.

Consequently, in 1779 I became part-owner of the privateer ‘Lucy’. And I was involved in others during the next 3 years. Overall, the risk was high and the return for some investors - here I speak of myself - was poor indeed. While ‘Lucy,’ for example, took upwards of a dozen prizes, when accounts were settled on her ventures, I was the loser by some £35! The spoils of war, indeed!”

On his involvement in the American Revolutionary War

“Well, there was one “dubious and difficult affair”.

Early one morning I was awakened with the news that men from two American Privateers had taken the Fort and were holding several of our men prisoner there. As Colonel of the Militia, I knew I must reply quickly and with determination. I sent orders to town that my Captains should get their men under arms. Word came back to me that our people were disheartened and inclined against resistance. However, I ordered that the privateer captain and his guard were to be taken as they advanced through the town. After an exchange of gunshot, the privateer Captain was indeed captured. I now had a basis for negotiation. Captain Cole - for such was his name - informed his men that our militia was ‘assembled and determined to fight’. I held firm on our demand that the invaders must depart, leaving the harbour and town as they had found them - and that for our part we would allow them 24 hours to make their escape. The invaders agreed to my terms and evacuated the fort while our militia marched in.”

On Religion

“I endeavour to always be ready to meet my Maker. I contrive to have the Sabbath free from business and other cares that I might attend the Meeting House - up to four times some Sundays. I have personally met every preacher to come to this town - many have dined or boarded with me, here in my home.

When I was young, in Connecticut, my family, and most others there, were Congregationalists. And, naturally, we brought our beliefs here with us - and for some 20 years got along well enough.

Now, I found more comfort with the recently arrived Methodist preachers. If you wish proof of my conversion, well consider the baptism of five of my children by the Methodist minister - all on the one day, here in this house. Now I am a trustee of the Methodist church - we sometimes meet here in this house.”